The women of the Brown Berets — Las Adelitas de Aztlán — break free and form their own movement.

Putting pen to paper, Hilda Jensen began her letter: “Hi, I’m the girl with the bandoleros.”

It was 2003 and she was writing to filmmaker Jesús Salvador Treviño from her home in Alabama. She had learned that the cover of his memoir, “Eyewitness,” had a photo of her as a teenager.

Through the years, she’d stumbled on images from the 1960s and ’70s, photos of her and her friends growing up in East Los Angeles and taking part in political actions, including the massive National Chicano Moratorium march and rally against the Vietnam War on Aug. 29, 1970. The photos were in newspapers, books, on a vinyl album cover and shared across the internet.

Jensen noticed that the men in those images were usually identified with their full names. In contrast, the women and girls who participated in the Chicano movement were most often collectively described as Brown Beret Chicanas. Only a few pictures bore their names.

The thought of women’s contributions to the Chicano movement going unrecognized bothered Jensen. She asked Treviño to be identified, and to include her maiden name: Hilda Reyes. He agreed without hesitation.

Established by teenagers of Mexican descent, the Brown Berets — a group akin to the Black Panther Party in dress and ideology — played a pivotal role in organizing residents of urban areas during the late 1960s and early ’70s. With a platform that centered the experiences of working-class Mexican Americans dubbed “Chicanos,” the Brown Berets rejected assimilation into European American society and stood against the Vietnam War and police brutality. They also demanded high-quality and culturally relevant bilingual education, helping lead massive walkouts at high schools on the Eastside.

At its peak, the Brown Berets had as many as 55 chapters throughout the country, including the Southwest but also in states such as Kansas and Minnesota. By 1970, however, the founding chapter was tearing at the seams. As the group planned demonstrations against the Vietnam War, female members began to question why they were largely excluded from leadership positions and relegated to behind-the-scenes, menial work.

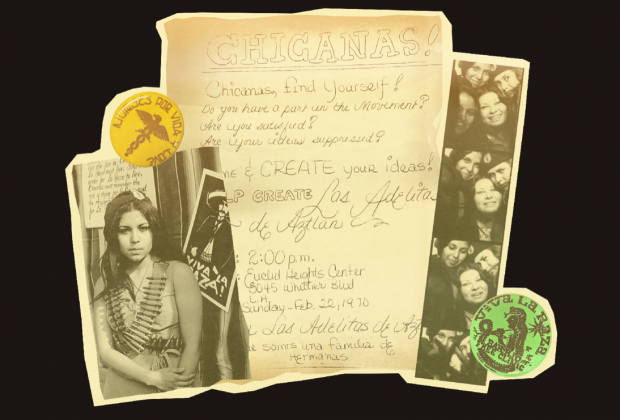

Undated photo strips show Gloria Arellanes, at left, and at center, with fellow Brown Beret members including, from clockwise: Lorraine Escalante, Hilda Reyes and Arlene Sánchez. (Special Collections & Archives, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, Cal State LA, Gloria Arellanes Papers)

In a letter addressed to the Brown Berets’ national headquarters, the women of the Los Angeles chapter collectively resigned on Feb. 25, 1970, citing “a great exclusion on behalf of the male segment.”

“We have been treated as nothings, and not as Revolutionary sisters,” they wrote. “We have found that the Brown Beret men have oppressed us more than the pig system.”

“It was really, really hard to leave. It led to a lot of fights. But it also felt very freeing.” says Gloria Arellanes, the first woman to resign from the group.

“I had reached a point where I had tried to make it good and make it work,” she says. “And I didn’t get that, so I had to stand my ground and say: ‘Ya basta. I’m done.’”

In a letter addressed to an official at the Brown Berets’ national headquarters, the women and girls of the Los Angeles chapter collectively resigned on Feb. 25, 1970, citing “a great exclusion on behalf of the male segment.” (Special Collections & Archives, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, Cal State LA, Gloria Arellanes Papers)

La Causa

While cruising through Whittier Boulevard one night, 18-year-old Arellanes and two friends were invited to the Piranya Coffee House in East Los Angeles. Soon they found themselves among members of the Young Chicanos for Community Action, a group that pushed for educational reform.

After two more visits, Arellanes and her friends joined the group, which was later rebranded the Brown Berets. “I’d never heard this kind of talk,” she says, “kind of militant, and a lot of, ‘We’re not going to take the police getting us anymore.’”

The group presented an alternative to her experience at El Monte High School, which was marked by racial conflicts and unequal discipline consequences between white and brown students.

“There was a lot of discrimination, a lot of racism,” she says, remembering routine brawls with a group of white students known as the “surfers.”

“The police would come into the hallways of the high school and just arrest the Chicanos,” she says. “They never arrested the white kids.”

In the classroom, Arellanes often felt invisible. She remembers waving her hand, hoping to be called on. “I never got acknowledged, so I gave up, and I said: ‘Forget this.’”

Through her work with the Brown Berets, Arellanes developed confidence in her abilities and found that she was able to galvanize volunteers. David Sánchez, the group’s founder, took notice and named her minister of Finance and Correspondence. She became the only woman on the leadership team.

The position, she says, put her in a gray area. Often, she was the “go-between” for the male Brown Beret leaders and the female membership. But this afforded her the opportunity to establish camaraderie with the other women and girls.

Alongside the other female members, Arellanes designed and edited La Causa, the Brown Berets’ community newspaper.

“We did all the artwork. We did all the lettering,” she says. “There are pictures of us around the table just talking and talking and doing our work. We always had a good time when the women got together.”

La Causa newspaper front pages.

In 1969, the Brown Berets established the East LA Free Clinic on Whittier Boulevard. Sánchez, who partnered with a health group to find professionals willing to volunteer and serve the community, tasked Arellanes with running the clinic.

Under her direction, the medical center — which was later renamed El Barrio Free Clinic — provided a wide range of medical services, including drug addiction counseling, immunizations, physical exams, STI screenings and even small surgical procedures. Health professionals also provided counseling for unwanted pregnancies.

“And we didn’t say: ‘Have an abortion’ or ‘Do this,’” says Arellanes, underscoring that patients were always informed of all their choices. This resulted in trouble with funding.

“We used to get money from the Catholic Church. And they came one time with a priest and said that they were taking the money away. I said, ‘Fine with me. I’m not going to give up what we do for people.’”

The clinic was also a site of activism. In 1969, the female members joined a hunger strike in solidarity with 26 prisoners protesting conditions at the Los Angeles County Jail.

It started as a peace march. But for the Moratorium generation, the day left protesters dismayed, disappointed and angry.

The soldier’s daughter

Jensen got involved with the Brown Berets at 14, when she was in middle school, and has fond memories of working with female members. They fundraised for the clinic, answered phones, sterilized tools and equipment and provided Spanish-English translation.

She first came to know about the group through Arlene Sánchez, her best friend at Hollenbeck Jr. High, and sister of Brown Berets founder David Sánchez.

In seventh grade, the two girls would often meet on the Sánchez family’s porch, listening to records and eavesdropping as David Sánchez and his friends ran meetings inside the house.

One day, Sánchez asked the girls to help distribute fliers. They spent the afternoon walking up and down Brooklyn Avenue, doling out leaflets for an event at the Piranya Coffee House. But when they asked Sánchez if they could go along to the event, he told them, “You girls are too young.”

The girls were undeterred. They talked someone into giving them a ride and, halfway through the event, the uninvited middle schoolers gingerly entered the coffee shop. “David was a little upset,” says Jensen, speaking by phone from Kingman, Ariz., where she moved in 2008. He immediately ushered the girls to a back room. Then he softened. He walked up to Jensen and his disobedient sister and said, “Go get yourselves a drink.”

The middle schoolers melted into a sea of smart, sophisticated faces, all sipping coffee and animatedly discussing politics. With cups of soda in tow, they feigned doing the same. Then bright lights flashed through the windows.

Jensen, now 67, recalls seeing Sánchez sprint out the door to see what was going on. She remembers seeing police officers and squad cars. “And they threw him against the car. They beat him up,” she says.

“But that was a constant thing” at the coffeehouse, says Jensen, who was held at a jail overnight after police raided the coffeehouse that night.

As a result, Jensen’s mother opposed her participation in the group. But there was no changing her daughter’s mind. Eventually Jensen’s mother supported her, going so far as to sew the female Brown Berets’ uniforms.

Wearing that uniform gave Jensen a sense of pride, “a sense of belonging,” she says, “with mexicanos, chicanos, something I didn’t have before.”

After photographers, including the now-acclaimed George Rodríguez, snapped pictures of her with a bandolier across her chest at Lincoln High School, Jensen became an icon. Her image was reproduced on book covers to raise funds for the Brown Berets, and since then she’s been featured on posters, buttons, books and much more.

At first, Jensen’s father bristled at her participation in demonstrations against the Vietnam War, reminding her that he had a Purple Heart for his service in the Korean War. They clashed. But then they began to talk in earnest. Through those conversations, Jensen learned that even in the trenches her father was segregated from white soldiers.

“You see, this is why,” Jensen told him, aghast at what he had endured.

“As I got older we mended our differences and we got more close,” she adds. “I was his caregiver and we understood each other, respected each other’s views.”

She said, he said

As the Brown Berets’ influence expanded, the role of women in the Los Angeles chapter remained circumscribed. Besides Arellanes, no other woman rose through the ranks. And there were no elections for leadership positions. Sánchez named himself prime minister and appointed fellow ministers at will.

Sánchez today says he had a reason for his governing style.“We saw that so many organizations fell apart because of the voting and because of the chisme [or gossip] and because of the arguments, which destroy most organizations,” he says. “So, we decided that we would have a semi-military organization and just decide on the mission — no arguments, no doubts. It was a lot faster, and it saved us a lot of problems.”

That structure, however, excluded the women and stifled disgruntled members’ concerns. Conflicts arose over the Brown Berets’ free clinic, which also served as its headquarters.

The Mission Furniture showroom on Whittier Boulevard is where the East LA Free Clinic was established. It is in the process of being named a historical building. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

According to Arellanes, men in the group often gathered there to drink and fraternize after hours. They never picked up after themselves, she says, leaving it up to the women who ran the clinic to hastily tidy up before patients arrived.

Arellanes took her concerns to Prime Minister Sánchez. “I would tell him: ‘The janitors have to clean up the mess, and guess who the janitors are?’” she says. “I was getting tired of that. So I asked David to talk to the men and tell them that they can’t hang around the clinic.”

Sánchez remembers it differently. In an interview with The Times, he says that male Brown Berets only gathered for drinks at the clinic on one occasion.

“I didn’t think nothing of it,” he adds, describing those members as “good guys” who merely got together to “drink a few beers.”

When asked if the men left the clinic ready to use the following morning, Sánchez says, “I think they went back and cleaned up the next day.”

Five decades later, Arellanes maintains that what she describes was routine behavior. It mattered, she says, because it not only created unnecessary work for the women, but tarnished the center’s reputation — one they’d built from scratch.

“We had established a very family-oriented clinic,” she says. To spread the word about the services they provided, she and other female Brown Berets went door-to-door through East Los Angeles. “The younger men participated with us,” she says, “but the older ones did not.”

Seeing no improvement with the situation at the clinic, Arellanes told Sánchez, “If you can’t clean them up, then I need to leave. And I will take all the women with me, probably, and maybe some of the younger men.”

“And that’s exactly what I did,” she says.

To this day, Sánchez maintains that the complaints outlined in the female Brown Berets’ letter were unfounded. He also holds that the resignation was a ploy to cover up a plan to steal the clinic. Arellanes, he says, was coached by “outsiders.”

“I don’t have a problem with the Berets anymore,” Arellanes says regarding Sánchez’s allegations.“I know they’ve claimed that I stole things from the clinic. When we left, all I took were the patient files, because of confidentiality reasons.”

The resignation letter speaks to this 50-year-old dispute. “Contrary to what the men are saying,” the women wrote, “that we are ‘temporarily suspended[,]’ we have officially resigned.”

Unwelcome ‘love’ letter

Dionne Espinoza, a professor at Cal State L.A. and expert on gender and sexual politics in Chicano youth culture, maps out the gendered division of labor in the Los Angeles chapter in her research on the Brown Berets. She also signals that sexism was not unique to this group, but rather a challenge women faced in organizations across the country, including the student group formerly known as MEChA and La Raza Unida, a political party.

“Women were denied leadership roles and were asked to perform only the most traditional stereotypic roles — cleaning up, making coffee, executing the orders men gave, and servicing their needs,” historian Ramón Gutiérrez, a professor at the University of Chicago, writes in an article on Chicano politics for the American Quarterly. “Women who did manage to assume leadership positions were ridiculed as unfeminine, sexually perverse, promiscuous, and all too often, taunted as lesbians.”

At San Diego State University, women had leadership roles in the campus Chicano student group. But as associate professor Adelaida Del Castillo wrote in “Mexican Women in the United States,” when it was announced that the former boxer and famed activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales would visit the university in 1970, the group deemed it “improper and embarrassing for a national leader to come on campus and see that the organization’s leadership was female.” Ultimately, it was decided that “only males would be the visible representatives for the occasion.”

Even when the men praised the women, their sexism showed. Consider this passage from “A Love Letter to the Girls of Aztlán” by celebrated Chicano attorney Oscar “Zeta” Acosta — a.k.a. “the brown buffalo” and Hunter S. Thompson’s Dr. Gonzo — in Con Safos Magazine, a leading Chicano literary journal.

“For months now if not for years we muy macho guys

of the movement have longed for your involvement in the

drinking of our booze smoking of our dope and most importantly

the making of our brown babies who shall bear our names and not yours …

“For now among other things I hear you now wish to

be my equal y mi camarada proposing an end to separation

and discrimination which of late you’ve learned to articulate so well …

“And so you write poems speeches and little bits of

propaganda which you’ve copied from some white woman’s

notes at the SYMPOSIUM ON THE CHICANA beginning as

it did and ending as it did with an attack on my machismo”

In response, “Una Chicana de Pittsburg” [A Chicana from Pittsburg, CA] wrote: “Dear Zeta: Your love letter sounds like a proposition, and not a very good one at that.”

When discussing the portrayal of female leadership in the Chicano movement — from Arellanes to United Farm Workers co-founder Dolores Huerta — Espinoza says that when examining historical moments, it’s as important to look at who passed out fliers, not just “the person talking in front of the microphone when there’s a press meeting.”

A group of their own

After leaving the Brown Berets, Arellanes — along with Jensen and her sister, Grace; Andrea and Esther Sánchez; Lorraine Escalante; Yolanda Solis; and Arlene Sánchez — founded Las Adelitas de Aztlán. The name referred to the soldaderas who fought alongside the men during the Mexican Revolution. They invited members of the community to join them and on Feb. 28, 1970, they made their public debut at the second anti-war moratorium in East Los Angeles.

In preparation for the event, they tried to learn the lyrics to a popular corrido titled “La Adelita.” But the song is really long.

“We forgot the words,” says Arellanes. “We always laugh about that.” With rain falling on them, the Adelitas hummed the tune.

Dressed in black and wrapped in rebozos, a long garment similar to a shawl, the women and teenagers marched while carrying white crosses bearing the names of Chicanos who had died in the Vietnam War.

Members of Las Adelitas de Aztlán at the second Chicano Moratorium protest against the Vietnam War on Feb. 28, 1970. At right is Hilda Reyes. They marched in the rain under a banner made by Gloria Arellanes and other members of the group. (Oscar Castillo)

Arellanes carried a cross with her cousin’s name, Jimmy Vásquez. Jensen, not yet 18, carried the name of Sgt. Richard Campos, whose body was unclaimed after its return from the war.

On Aug. 29, Jensen, Grace and three other Adelitas joined the crowd on the march to Laguna Park for the National Chicano Moratorium, the third in a series of anti-war demonstrations that had taken place in East Los Angeles without incident. But as thousands of people huddled around the stage waiting for the day’s programming to begin, Grace noticed smoke.

Wondering if there was a fire, they went to see what was happening. The smoke was from tear gas canisters, which police officers were hurling at demonstrators. People ran in all directions. A police officer began to chase after Jensen and her friends. He was just a couple of feet behind them, she says, remembering feeling a wave of air from the baton on her back.

As they ran, men in the crowd of protesters distracted the officers, allowing them to escape.

Then Jensen’s group noticed some women and their children entering a nearby restroom. “We’ve got to get them out of there,” said her sister Grace, “or they’re gonna get hurt.”

Inside the bathroom, the mothers and children struggled to get water from the faucets. They were trying to wash their faces after being tear gassed, but the trickles of water that came out weren’t enough to even get a handful of water, Jensen says.

“So we’re in there and these kids, they’re crying for dear life because they’re scared,” she says. The mothers cried with them, “because they don’t know what to do.”

As Jensen and her companions devised an escape plan, a police officer shot a tear gas canister into the restroom. It landed in the stall farthest from them, but it didn’t go off. Startled, the pained children screamed even more.

Male protesters engaged the officer outside the restroom, hurling whatever was at hand at him in an attempt to distract him. Another officer launched another tear gas canister into the restroom.

By then, Grace had ordered the group to run. As they fled, Hilda’s shoe fell off and was hastily returned to her.

“If we would have stayed there, we would have been — gosh, I don't even think we would have made it.”

hilda jensen, 67

They ran into David Sánchez along the way, who ordered them to go home. A friend told the girls to go to his family’s apartment and stay there until it was safe. They left just before streets were barricaded off.

“If we would have stayed there,” Jensen says, “we would have been — gosh, I don’t even think we would have made it.”

Arellanes was on the stage when the chaos at the park started.

She saw a wave of people run in one direction, then the other. “And then it went back and then boom! People were screaming and running. I got tear gassed immediately. And I could not see. I could not breathe,” she says. “Somebody got a wet T-shirt and put it on my face.”

She was taken onto a bus with others. They went back to the Brown Beret office, where people from out of town were also headed. The group had arranged transportation and places for them to stay, bringing people from all over the United States — including Seattle, San Antonio, Denver and Chicago. Violence from the day would leave three dead.

“How did I get home?” Arellanes wonders. “I don’t know. I don’t remember much after that.”

Gloria Arellanes’ former beret, which is now part of a collection at Cal State LA.

Leaving the past behind

Las Adelitas de Aztlán dissolved that year.

“Everybody kind of went their own way,” Arellanes says. “I went away for 40 years. I couldn’t handle that people were killed.”

Arellanes went on to open another clinic, La Clínica Familiar del Barrio, on Atlantic Boulevard, with an entirely new staff, some of whom went on to pursue careers in health and social work.

Jensen also stepped back and decided she would never join another organization.

“When the [original] clinic closed, that was devastating for me,” she says. “When you’re that young and this is all you have — really, and this is all you know — working for the community and it’s closed down like that, that was the saddest thing.”

After her first daughter was born in 1972, her decision to stay away from organizing was reinforced.

“After the Chicano Moratorium, I said no way am I going to put myself in jeopardy ever again,” Jensen says. “Because that’s how scared I was.”

Surrounded by plants at her home in El Monte, where a Bernie Sanders 2016 sign still adorns her front porch, Arellanes, now 74, says it wasn’t until former Brown Beret Rosalío Muñoz contacted her about participating in commemoration of the Chicano Moratorium in 2010 that she came back on the scene.

With two children, schooling and newfound focus on learning about her Tongva roots, Arellanes warned Muñoz that she was now a different person.

Since then, Arellanes has participated on dozens of panels and provided an oral history of her lived experience. She also donated a large collection of documents, photographs, posters and even a brown beret to the Cal State L.A. Special Collections library. The Gloria Arellanes Papers are now a part of the library’s “East L.A. Archives,” which also includes another Brown Beret-related collection from co-founder Carlos Montes.

“I’ve been talking with the Berets,” she says. “I just very clearly said, ‘I don’t care if you don’t like me, but if we want to get any place, we’ve got to be united now. We’ve got to have solidarity and unite. Forget all the personal stuff. Let it go. Gosh, it’s been 50 years. Let it go.”

What she hasn’t forgotten is the pain of Aug. 29, 1970. When scholars first began approaching her to talk about her experience in the Chicano Movement, they often showed her videos of the Moratorium. “And I would just sit and cry,” she says.

Back in the 1960s and ’70s, Arellanes adds, she owned a rifle. She used to go to the mountains for target practice.

After the Moratorium, she threw it out. “To see all that tragedy and that violence and get tear gassed, to see people screaming and running for their lives. It destroys something in you when you see that much pain.” Later, when Arellanes raised her two sons, she wouldn’t even let them have water guns.

One image remains embedded in her memory: “It was at the park. There was a lot of paper, a lot of debris. There was a wheelchair, tipped on its side. Nobody in it. You know, somebody carried somebody. That always stayed on my mind.”

A new generation

Although Las Adelitas de Aztlán didn’t last long, they’ve left a legacy that others feel connected to even 50 years later.

“I ran into a lot of young women who go under the name Las Adelitas,” Arellanes says. “And they were so honored to meet me. And I said: ‘Why? We didn’t do anything.’ You know, it never took off, but for some reason it stayed for women to identify with.”

Starting in 2018, Arellanes has opened up at three of the Los Angeles Women’s Marches, inviting women in recently formed Brown Beret chapters to join her. She starts by acknowledging her Tongva ancestors.

Now, 50 years later, the events of the Aug. 29 Chicano Moratorium are ever more present in Jensen’s life.

“When I see Black Lives Matter, and I see all the disruption and the cops and the people being hit with tear gas and all that, I cringe,” she says. For her, it’s like living that day all over again. “You don’t forget these things. You stay scarred.”

In the summer of 2016, poets and musicians, led by Martha González of the band Quetzal, performed at a concert called “Chicana Moratorium: Su Voz, Su Canto,” inspired by the stories of former Adelitas.

Musician Alice Bag, a pioneer in the punk rock movement, honored the women by singing an as-yet unrecorded corridoabout Arellanes and the Adelitas.

“Su boina café ya se la quitó [She’s taken off her brown beret]

Pero también sin boina ella nos inspiró [But even without the beret, she inspired us]

A Chicanas jovencitas [Young Chicanas]

Y todo tipo de mujer [And all types of women]

A las nuevas Adelitas [The new Adelitas]

Que no se dan por vencer [Who don’t give up]

Y luchan por conseguir [And fight to achieve]

Liberación verdadera” [True liberation]